Yoga Tips For Holiday Digestion

As a vegetarian married to a vegan, I’ve grown accustomed to dealing with a great deal of well-meaning fretting from both my mother and my mother-in-law when my husband and I visit our families for the holidays. My mother brought me up on the USDA’s “Four Food Groups” nutritional model of the 1970s; in her mind, a proper dinner consists of a meat-based main dish accompanied by a vegetable, a plant-based starch, and white rolls with margarine. There are no exceptions to this rule, and she prides herself on having provided me, my three sisters and our father with a “proper” dinner every single night for 20 years. And don’t get me wrong, I appreciate it.

As a vegetarian married to a vegan, I’ve grown accustomed to dealing with a great deal of well-meaning fretting from both my mother and my mother-in-law when my husband and I visit our families for the holidays. My mother brought me up on the USDA’s “Four Food Groups” nutritional model of the 1970s; in her mind, a proper dinner consists of a meat-based main dish accompanied by a vegetable, a plant-based starch, and white rolls with margarine. There are no exceptions to this rule, and she prides herself on having provided me, my three sisters and our father with a “proper” dinner every single night for 20 years. And don’t get me wrong, I appreciate it. The idea of coming home from a long day of work and cooking a full dinner for six people even once a week makes me want to get into child’s pose and stay there. My husband’s mother was a pediatric nurse who often worked the evening shift, so his father—not a man who grew up cooking— was usually responsible for providing nightly dinner for three growing boys, on a budget. Unsurprisingly, to this day it is hard for my husband’s parents to conceive of a family dinner that doesn’t revolve around two to three pounds of hamburger incorporated into a recipe off the back of a box.

Like many loving mothers of adult children, my mother and my mother-in-law remain consumed with concern about what and when and how often my husband and I eat, especially when we’re in their homes. Cooking and serving food is a way of showing love, and it is frustrating to both of them to be denied the pleasure of making our favorite childhood foods now that we no longer eat many of them. Even more so, I think their concern stems from a phenomenon common to non-vegetarians, namely, a sincere worry that vegetarians and vegans simply aren’t getting sufficient nutrients. It’s been well over a decade since we both stopped eating meat, but at family functions the question still arises with seemingly unassuageable vexation: “Will there be anything for you to eat?!” Unsurprisingly, the issue assumes an even greater intensity around the holidays, particularly Thanksgiving (which, in my husband’s family, is celebrated as less of a holiday and more of a 14-hour competitive eating decathlon).

Two years ago, after remaining at home in New York City for Thanksgiving for logistical reasons and fielding agitated FaceTime calls from both of our mothers –-“Did you get enough to eat?!” (his) “What did you even eat?!” (mine), we decided to put our parents’ minds at rest once and for all. After a bit of persuading, we convinced our families to let us cook them vegetarian/vegan holiday meals last year—we visited his family for Thanksgiving in mine for Christmas— to close the book once and for all on the question of whether it’s possible to uphold the American holiday tradition of gluttonous overindulgence without eating animal products.

They were skeptical at first, but after enjoying seconds of my Brussels sprouts gratin, thirds of his mushroom-sage stuffing, and subsequently passing out on the couch only to awaken two hours later for one more slice of dairy-free pecan/pumpkin pie, we had them convinced: it’s not only possible to overdo it at a vegetarian Thanksgiving, it’s positively easy. As a yogi, I try to practice brahmacharya—sometimes defined as discipline over the impulse towards excess—but I am only mortal, and my self-restraint tends to fly out the window when confronted with garlic mashed potatoes.

All of which is to say, whether vegetarian, vegan, pescatarian or omnivore, most of us have a tendency to overindulge at this time of year. I teach at a college, and by the time I’m finished with the fall semester I have usually attended at least four work-related holiday parties, having managed to resist housing a bucketful of my colleague Professor Yao’s home-made Chex mix at exactly none of them. Brahmacharya is all well and good, but you know what’s also good? My friend Dave’s praline pecans.

If you’re anything like me, dramatically increasing your intake of sugary, fatty and processed foods tends to wreak havoc on your digestive system. We can’t put a halt to holiday fun (who would want to?) and I, at least, probably cannot stop myself for reaching for that second White Fudge Oreo (they’re only in stores once a year!). Thankfully, asana and yogic techniques are available to aid and improve our digestion, as well as mindfulness practices which can help us truly appreciate the sensory ritual of eating. Read on for five tips for improving digestion with yoga this holiday season.

1) Add Twists to Your Asana Practice

Let’s not beat around the bush: between the eggnog and the port-wine cheese balls, I tend to consume a lot more dairy than usual during the holiday season, which tends to, um, cause my inner elves to slooooow down production in the ol’ toy shop, if you take my meaning. In other words, I get constipated, and when I do, I make sure that my on-the-mat practice includes plenty of twists. Just make sure you’re doing them correctly to aid in… efficient toy production.

Twists aid in the movement of waste through your colon, as long as you begin by twisting to the right side. Starting this way targets the ascending colon, helping it to stretch and send waste across the transverse colon. Then, when you twist to the left, your body encourages the waste to continue on to the descending colon and finally into the sigmoid colon, where it becomes ready for elimination. Try incorporating parivritta ardha chandrasana (revolved half-moon) and parivritta trikonasana (revolved triangle) into a warrior sequence, or add parivritta utkatasana (revolved chair) into a standing balance sequence.

2) Boost Your Agni

Agni is the Ayurvedic term for “digestive fire” (meaning your body’s capability to digest food easily and completely). Undigested or poorly digested food results in the body’s production of a toxic by-product called ama, which inhibits immunity. (For more on agni, ama, and boosting immunity with yoga, refer to our post “Yoga Hacks for Allergy Season” here.)

Healthy digestion requires strong agni, and strong abdominals beget strong agni. Asana that target the abdominal muscles include phalakasana (plank pose) purvottanasana (upward plank) utthtita trikonasana (extended triangle) and virabhadrasana (warrior) III. Strengthening the lower back muscles will contribute to your core strength, so make sure that your on-the-mat practice includes plenty of vinyasas (adho and urdhva mukha svavasana are both excellent for increasing back strength) as well as danurasana (bow), salabhasana (locust) and/or setu bandha sarvangasana (bridge).

In addition, try practicing the pranayama/asana hybrid agni sara. Agni sara (literally “essence of fire”) utilizes the solar plexus, lower abdominals and pelvic floor muscles, stimulating the digestive system and aiding in proper elimination of waste. You can view a step-by-step guide to agni sara here. For beginners: start in sukhasana or malasana and contract the lower abdominals. Breathe deeply into the belly and pelvic floor, pulling the navel firmly towards the spine on the exhale and relaxing the belly fully on the inhale. Three rounds of ten breaths—ideally on an empty stomach—are sufficient.

3) Utilize Pranayama to Reduce Stress

Over-indulgence in rich or sugary holiday treats, alcohol and/or gluten and dairy can result in bloating as well as constipation. But bloating can also be a by-product of stress, and stress can inhibit effective digestion. There’s a reason the gut is often referred to as the body’s “second brain.” Acute stress directs blood flow to away from gut to the brain and limbs, and chronic stress can cause imbalances in beneficial gut bacteria, as well as inflammation.

There are many aspects of yoga that reduce stress, but deep belly-breathing in particular releases tension in the abdomen, allowing for increased blood flow and aiding in digestion, which in turn reduces bloating. A simple breathing exercise that targets the belly is Dirga Pranayama, or three-part breath. To practice Dirga Pranayama, find an easy seat with a straight back and a hand loosely placed on your belly. Inhale deeply and slowly, imagining that you are filling your belly, ribcage, and upper chest completely. Then exhale equally slowly, “deflating” the upper chest, ribcage, and belly. (Note: of course, you cannot actually breathe into your belly! But you can feel the sensation of breathing into your belly by practicing Dirga Pranayama, which in turn can help your abdominal muscles relax.) Another effective way to feel the breath drop low in the body is to find a comfortable child’s pose with relaxed arms, and inhale slowly with the intention of feeling the sensation of expanding your lower back with your breath. If it’s comfortable for you, separate your thighs so that your belly can “flop” between them.

4) Plan Ayurvedic Holiday Meals

Happily, Ayurveda already involves eating seasonally and regionally, and many of the traditional holiday dishes associated with Thanksgiving and other holiday meals are already based around fall harvest produce in North America. Yams, Brussels sprouts, carrots and other root vegetables are all in season in the autumn and can contribute to a balanced holiday meal while supplying nutrients without reducing agni. Even potatoes—sometimes regarded as a blanket no-no in Ayurvedic cooking—can take their part on your table, as long as you prepare them according to your dosha: add oil or other fat for Vata, limit fat and add warming spices for Kapha. Potatoes are basically neutral for Pittas, so go ahead and have that second scoop!

In addition to eating seasonally, keep your holiday meal Ayurvedically sound by including the six tastes: sour, salty, sweet, pungent, bitter and astringent. The fatty, moist recipes associated with Thanksgiving dishes will help to balance the dry, cold Vata season in which the holiday falls. Just make sure you include bitter, pungent, and astringent tastes as well, to balance the flavor and nourish the dhatus. Ayurvedic holiday recipes, including Thanksgiving favorites, can be found here.

5) Try Following a Sattvic Diet

Following a Sattvic diet at points throughout the year can certainly ease radical eating disparities during the holidays. In Ayurvedic philosophy, there are three qualities, or gunas, that exist in all of nature: rajas, tamas and sattva. With regard to nutrition, these qualities manifest as stimulating rajasic foods (spicy, salty, or bitter tastes), enervating tamasic foods (bland, heavy tastes, or anything artificial or stale) and purifying sattvic foods (fresh, calming, and easily digestible).

The term sattvic can refer to an entire lifestyle of intentional ritual, meditation and philosophy. Serious yogis will often maintain a sattvic diet for months or even years at a time, or undertake a sattvic cleanse, which can be intense and should be conducted under the supervision of a professional Ayurvedic practitioner. But we can all add elements of sattvic eating into our daily diets to improve digestion and wellbeing. Here are some simple suggestions to get digestion back on track after a holiday meal, keeping in mind that you may need to make adjustments if you are currently eating to balance your particular dosha:

• Eat fresh, organic produce. Try to base meals around fresh ingredients and whole foods.

• Eat less meat. Try beans and lentils as alternate sources of protein.

• Cut down on refined sugar and processed foods. Consider honey or molasses as an alternative to sugar.

• Reduce your intake of alcohol and caffeine. Alcohol is enervating, or tamasic, and caffeine is stimulating, or rajasic. Reducing both helps to bring the both mind and the gut into a balanced, calm sattvic state.

• Pay attention to where and how your food is prepared. Truly sattvic food is prepared in a pleasant atmosphere, with intention and love. While this might not be practical for every meal, especially if you frequently eat outside your home, you can start by making one sattvic meal day for yourself every day, such as a simple breakfast of whole oats, fresh milk, and some honey or fruit.

While brahmacharya is certainly a virtue, even the most disciplined among us can fall prey to the perils of holiday revelry, leaving our tummies to pick up the proverbial tab. Happily, whether we’re planning ahead or looking back in regret, yoga and Ayurveda offer plenty of tools for soothing and regulating digestion. So, bring on those special edition White Fudge Oreos! After all, they’re technically vegan, and this year I’ll stop after one. Or two. Definitely not more than three.

For an intro to Ayurveda, please join us for Prema Yoga Therapeutics Essentials February 7 -March 1, 2020, or for a more in-depth explanation in our annual Ayurvedic Yoga Therapy Therapy Training.

—————-

Online Sources:

___________________________________________________________________________________

Molly Goforth is a yoga and meditation teacher and a student at Prema Yoga Institute. She specializes in accessibility and trauma-informed yoga teaching and practice.

Back To School: Yoga To Increase Memory and Focus

In yogic philosophy, a sankalpa is a solemn vow, made in the heart and forged by the will. A yogi sets a sankalpa to focus the mind and heart on a particular goal. Like much of Hindu philosophy, the idea of sankalpa is complex and layered, but the Western practice of conscious intention-setting that has gained popularity in the past few decades could be considered a simplified conception of sankalpa, with the caveat that a sankalpa is meditative and process-oriented. When you set a sankalpa, the effort you make towards your goal is as important as achieving it.

In yogic philosophy, a sankalpa is a solemn vow, made in the heart and forged by the will. A yogi sets a sankalpa to focus the mind and heart on a particular goal. Like much of Hindu philosophy, the idea of sankalpa is complex and layered, but the Western practice of conscious intention-setting that has gained popularity in the past few decades could be considered a simplified conception of sankalpa, with the caveat that a sankalpa is meditative and process-oriented. When you set a sankalpa, the effort you make towards your goal is as important as achieving it.

The beginning of a new year seems like the natural time to set a sankalpa, so why am I speaking about sankalpa in September? Good question. The world runs on a wonderfully varied collection of calendars. While most of us follow the Gregorian calendar in secular life, some of us also follow an additional cultural or religious calendar, and may find ourselves ringing in the new year twice. The Chinese New Year generally arrives in February, while many Pagans welcome a new year on November 1st. For Roman Catholics, the liturgical year resets at the end of November with the advent of, well, Advent. Many cultures observe a new year in the spring, which makes sense: as the earth literally renews itself, our communal measure of time does, as well. But if you’re like me, there is one time of year that is indisputably “sankalpa season”—a few short weeks that make me eager for change in a way that no calendar-official new year can, and that time is back-to-school.

It’s been decades since I’ve actually returned to school at the end of the summer, but the early weeks of September still feel full of anticipation and promise for me in a way that January just can’t match. An unofficial straw poll among my yogi friends reveals that most of us get the urge to shop for unnecessary school supplies around this time each year. If Reddit’s discussion forums are any indication, acute back-to-school nostalgia is a bona fide seasonal malady; the aspect of school that adults seem to miss the most is the feeling of working steadily towards a concrete goal, and I get it. As T.K.V. Desikachar says in The Heart of Yoga, “Taking an intelligent approach means working toward your goal step by step.” Perhaps the most enriching part of my yoga therapy journey so far has been the luxury of being a student again, and the satisfaction of vinyasa krama: learning via an organic, stepwise progression based on me, rather than learning as fast as I can to solve a problem or produce a result, as I do in my work life.

So I encourage you to reclaim this back-to-school season for yourself: one of yoga’s great charms is that there is always, always more to learn. This fall, give yourself the gift of a sankalpa: set an intention to broaden your yogic knowledge and fulfill it. And whether you find yourself with a pen in your hand or a foot behind your head, keep in mind these facts about how your asana and meditation practices help you learn, both on the mat and off.

1. Meditation Can Increase Your Ability to Focus, Even If You’re Anxious

Life is fraught with stress already, and the challenge of learning something new can aggravate our body’s stress response, especially if we’re experiencing a doshic imbalance, or have a predisposition towards anxiety (remember: fall is Vata season). According to research performed at the University of Waterloo, just ten minutes of mindfulness meditation every day can result in meaningful improvements in focused attention, especially among those with a tendency towards anxiety. Mengran Xu, a Ph.D. candidate who conducted the study, noted that

"Mind wandering accounts for nearly half of any person's daily stream of consciousness...for people with anxiety, repetitive off-task thoughts can negatively affect their ability to learn, to complete tasks, or even function safely.”

Unsurprisingly, given that the purpose of mindfulness meditation is to notice our thoughts without attaching to them, Xu’s study demonstrates that daily mindfulness meditation helped anxious individuals divert their attention away from their mental chatter to better focus on the task at hand. (Xu might not have been previously familiar with sutra 1.2, “Yogas chitta vritti nirodha,” but he certainly demonstrated it!). In addition, the down-regulating effects that meditation and restorative yoga have on the parasympathetic nervous symptom contribute to stress reduction, which in turn increases cognitive function.

2. Hatha Yoga Can Improve Your Memory

According to research published in The Journals of Gerontology, practicing Hatha yoga can improve your ability to sustain attention, which in turn improves your brain’s ability to recall information.

In addition to recall, those participants in the cited study at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana who spent eight weeks taking regular Hatha yoga classes subsequently showed marked improvement in mental flexibility and task-switching, significantly outperforming a control group who performed non-yoga toning and stretching exercises for the same period.

The likely key to the difference in performance won’t come as a surprise to yogis: breath. According to Neha Gothe, who led the study,

"Hatha yoga requires focused effort in moving through the poses, controlling the body and breathing at a steady rate. It is possible that this focus on one's body, mind and breath during yoga practice may have generalized to situations outside of the yoga classes, resulting in an improved ability to sustain attention."

In other words, dharana and drishti on the mat lead to concentration and focus off the mat, which sharpens your memory. This is excellent news, whether your sankalpa is to master the Sanskrit alphabet or the consistent location of your phone.

3. Yoga Is (Much) Better for Your Brain than Aerobic Exericse

Exercise has long been touted as beneficial for neurological and mental health. But not all exercise is equally helpful. In fact, when it comes to brain benefits, studies suggest that yoga isn’t simply superior to aerobic exercise, it’s in an entirely different league.

According to research reported in The Telegraph, participants who practiced twenty minutes of Hatha yoga demonstrated more gains in reaction time and accuracy on cognitive tests—including the ability to “focus their mental resources, process information quickly and more accurately and also learn, hold and update pieces of information”—than after performing an equivalent amount of aerobic exercise (jogging on a treadmill). Moreover, unlike the post-yoga testing, the post-treadmill testing showed “no significant improvements in working memory and inhibitory control scores.” In other words, not only will you learn faster and retain information longer because of your yoga practice, you’ll remember to raise your hand before you speak, and you’ll be less likely to pass notes in class!

Considering all the ways your yoga and meditation practice boost your learning capacity, you’d be foolish not to take advantage of “sankalpa season” and resolve to learn something new this fall. Ayurveda, Anatomy, Philosophy, specialized yoga, such as pre-natal or trauma-informed: the possibilities are almost endless. I’m so excited for you, I’m mentally packing you a sattvic lunchbox already! Just remember, what’s true on the mat is true in the classroom as well: the effort you expend is as important—if not more so—than your goal.

—————-

A sankalpa is the first step in the deep meditation known as yoga nidra, or yogic sleep. More information on yoga nidra can be found here.

Online Sources

The Journals of Gerontology, Series A

___________________________________________________________________________________

Molly Goforth is a yoga and meditation teacher and a student at Prema Yoga Institute. She specializes in accessibility and trauma-informed yoga teaching and practice.

Yoga Nidra

Yoga nidra is not what you think. It was created by Swami Satyananda Saraswati in the 1960s as a result of his being able to remember chants that he did not recall being exposed to. It turns out that he was exposed to them while he slept and young boys chanted them at a monastery in India where he was stationed. Ancient yogis, indeed Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras (1:38) make mention of reaching samadhi through contact with sleep and dreams. This is one piece of yoga nidra, which is often referred to as yogic sleep.

Yoga nidra is not what you think. It was created by Swami Satyananda Saraswati in the 1960s as a result of his being able to remember chants that he did not recall being exposed to. It turns out that he was exposed to them while he slept and young boys chanted them at a monastery in India where he was stationed. Ancient yogis, indeed Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras (1:38) make mention of reaching samadhi through contact with sleep and dreams. This is one piece of yoga nidra, which is often referred to as yogic sleep.

Swami Satyananda Saraswati realized that sleep was not a state of total unconsciousness. “When one is asleep, there remains a state of potentiality, a form of awareness that is awake and fully alert to the outer situations. I found by training the mind, it is possible to utilize this state.” ( p. 3) In the yogic view of consciousness, humans primarily focus on the aspects of our experience and therefore brain that involve the ego. However, there are other states of awareness - the subconscious and unconscious mind - that are not organized through the ego, yet are part of us and our experience. Most people do not have awareness of, access to, or skills to work with this part of themselves. Yoga nidra is a system for working with all parts of our consciousness.

Yoga nidra is a method of pratyahara (p.29), the fifth of Patanjali’s eight limbs of yoga, withdrawal of the senses. Yoga nidra is done in savasana, with the eyes closed. It is important to have a teacher speaking the instructions to you or for you to be listening to the instructions via a recording. Yoga nidra requires the relaxation of the thinking mind. You can not think through the sequences yourself. You must listen to them. The first instruction is to focus your attention on external sounds, which in effect withdraws the other senses. The instruction is to move your attention from sound to sound with a witnessing attitude - do not analyze or think -- just witness the sounds. Soon, the mind grows tired of this and you drop into a deeper relaxation.

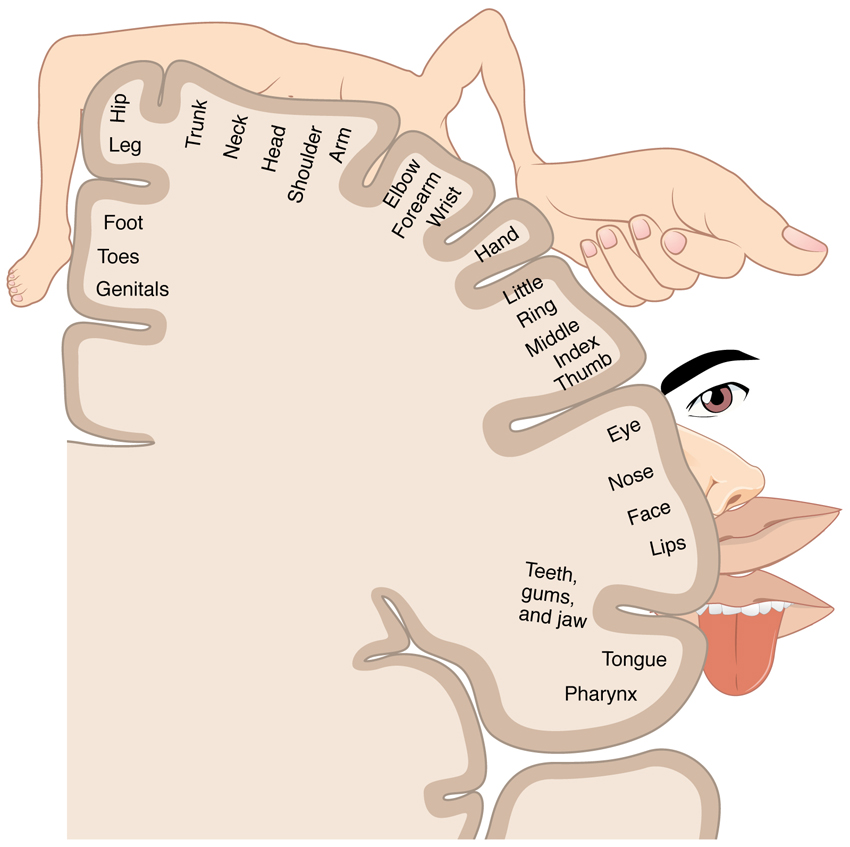

This is when one of the defining features of the yoga nidra practice takes place: the rotation of consciousness. Nyasa, a trantric practice, taught a very specific and quick rotation of one’s awareness through body parts and with a mantra for each body part. The idea was to instill divine consciousness in each body part as the mantra was chanted. The specific sequence is based on the motor or cortical homunculus, which is the somatotopic organization of the motor cortex in the brain. Each part of the brain is identified with motor or sensory input from a specific part of the body in a specific sequence. [see image] The image is a distorted view of the human body because it shows the order and intensity of the sensory processing that takes place in each space along the motor cortex.

By rotating your consciousness through a sequence which follows the motor cortex homunculus, you heighten your awareness of the body in order to stimulate the brain, which induces physical relaxation as well as clearing the nerve pathways from the brain to the body. Further to the deeper relaxation, a “dissociation of consciousness from the sensory and motor channels of experience occurs.” (p.38) This continues the practice of pratyahara, withdrawing the senses. The body is relaxed, the senses withdrawn. The key here is to remain aware -- not to drift into sleep, but to become deeply relaxed, with the senses withdrawn and completely conscious of your experience. This is where the mind training comes in. “When the mind dissociates itself from all the sensory channels, it becomes very powerful, but then it needs training. Unless involuntary systems of the brain have been trained, there is practically no difference between yoga nidra and sleep.” (p. 30)

From here, yoga nidra directs you to become aware of your breath, again another practice intended to bring you into a deeper state of relaxation. Then the practice instructs you to feel your body in contact with the ground and to feel it being very heavy. Yoga nidra always starts with heaviness, instructing you to feel the experience of heaviness and then feel its opposite, lightness. The practice flows through several sensory opposites and then turns to emotional opposites (love-hate; sadness-joy, etc). The instruction is to experience these opposites, one, then the other, then both at the same time - not to think about them, but to experience them. This is a kind of mind training, creating new neural pathways that allow you to hold the experience of opposites together witnessing that they can exist not as one or the other but both at the same time. This is referred to as training in the “transcendence of duality” (p. 42) which develops a mature personality, balanced outlook, and calm demeanor.

Then yoga nidra instructs you to experience a series of images, named by the teacher. The images are usually symbols of universal archetypes. “Words and concepts are the language of the conscious ‘intellectual’ mind. The subconscious mind has a language of its own based on symbols, colours, and sounds.” (p. 25) While learning yoga nidra, one often finds that when images are suggested by the teacher, other distracting images come up. These are from the unconscious, the ego and “they are often the root cause of tension.” (p. 46) By viewing this image in a detached way “as though one were merely watching a movie” the ego will become inactive during the practice and will no longer identify with the attachments, aversions, and inhibitions that produced the secondary images. This is a kind of purging which releases tension.

The primary purpose of yoga nidra is to release tension. Everything we do or don’t do outside our practice creates some kind of tension - mental, muscular, or emotional tension. We often think that relaxing is reclining in a chair or couch with some kind of drug -- coffee, tea, alcohol, nicotine, food -- and watching a screen or reading something. From the yogic perspective, this is merely sensory diversion (that creates more layers of tension) and not relaxation. “For absolute relaxation you must remain aware.” (p.1) Much of our suffering is caused by stress and stress related diseases because we have had no method and no training in real relaxation. Yoga nidra is the method for real relaxation. The final suggested image in the practice is one that induces the experience of calmness and peace.

There is one other critical component to the practice of yoga nidra and that is the resolve (sankalpa in Sanskrit). The resolve is made entirely by you and you bring it to mind at the beginning, right after the initial relaxation by focusing on external sounds, and then again after the final image. The resolve is a short statement which is impressed into the subconscious mind when it is receptive, when you are relaxed and have started to withdraw your senses. The resolve is like a seed that you plant at the beginning of practice and the practice is watering that seed. Statements such as, “I am transformed” or “ I am successful in everything I do” are good examples of the brevity and directness of one’s resolve. The resolve is always present tense.

Like preparing the garden, you must be prepared, receptive in order for your seed or resolve to grow and actualize. The practice of yoga nidra makes you receptive by withdrawing the senses, developing a witnessing attitude, opening the whole mind - subconscious and unconscious, while remaining clear, alert, and aware. “The science of yoga nidra is based on the receptivity of consciousness. When consciousness is operating with the intellect and all the senses, we think we are awake and aware, but the mind is less receptive and more critical.” (p. 29)

True and deep relaxation has the potential to be transformative both in terms of the restorations that can occur and also through the use of specific resolves when the body and mind are at their most receptive. A yoga nidra session lasts between 20 and 40 minutes and can build a foundation of resilience within you.

Resources

The quotes in this blog are from Swami Satyananda Saraswati’s book Yoga Nidra published by Yoga Publications Trust, Bihar India. 2001-2012.

Richard Miller, PhD.’s book Yoga Nidra is another good resource. It also has audio recordings of yoga nidra practices.

Image credit: By OpenStax College - Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions Web site. http://cnx.org/content/col11496/1.6/, Jun 19, 2013., CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30148008

——————————————————————————————————-

Deb McDermott is a first-year student in Yoga Therapy at Prema Yoga Institute. She has been a Yoga teacher for 20 years and recently completed a 40-hour training on Trauma Center Trauma Sensitive Yoga (TCTSY) with David Emerson and Jenn Turner.